|

|

The Prime Minister's recent criticism of the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) and its architect, Jawaharlal Nehru, has ignited a complex and multifaceted debate about India's historical and contemporary relationship with Pakistan, water resource management, and the legacy of its founding fathers. Modi's assertion that Nehru himself acknowledged the treaty's lack of benefit to India, coupled with accusations of partitioning the country twice – once through the Radcliffe Line and again through the IWT, which allegedly allocated 80% of the Indus River's water to Pakistan – raises fundamental questions about the treaty's fairness, its long-term implications for Indian agriculture, and the decision-making processes of the Nehruvian era. This critique not only revisits a decades-old agreement but also underscores the current government's assertive stance on issues of national interest, particularly concerning water resources and cross-border relations. The IWT, signed in 1960 after nearly a decade of negotiations mediated by the World Bank, stands as a landmark agreement between India and Pakistan, aiming to prevent disputes over the utilization of the Indus River basin's water resources. The treaty allocates the Western Rivers (Indus, Jhelum, Chenab) primarily to Pakistan and the Eastern Rivers (Ravi, Beas, Sutlej) to India, while also establishing mechanisms for cooperation and dispute resolution. Despite its longevity and perceived success in avoiding water-related conflicts, the IWT has faced periodic criticism and calls for revision, particularly in the context of changing geopolitical realities, increasing water scarcity, and the rise of cross-border terrorism. Modi's remarks highlight a growing sentiment within certain segments of the Indian political landscape that the treaty may have been overly generous to Pakistan and that it needs to be re-evaluated in light of India's current water needs and security concerns. The Prime Minister's comments are not isolated. Jagdambika Pal, a BJP MP, echoed these sentiments, characterizing the treaty as a 'betrayal' by Nehru and criticizing the lack of parliamentary approval. Ravi Shankar Prasad, another BJP leader, further amplified the criticism by pointing out that Nehru's government allegedly gave Rs 80 crore to Pakistan along with the treaty, alluding to a perceived appeasement policy. This concerted critique from within the ruling party indicates a strategic effort to reassess the historical narrative surrounding the IWT and to potentially pave the way for a more assertive approach to water sharing with Pakistan. The legal dimension of the IWT has also come under scrutiny. India's rejection of the recent award issued by the Hague-based Court of Arbitration, citing a lack of jurisdiction, legitimacy, and competence, underscores the complexity of international arbitration in the context of bilateral treaties and sovereign rights. This stance signals a willingness to challenge international legal interpretations that India perceives as detrimental to its national interests. Furthermore, India's decision to place the IWT in abeyance following the Pahalgam terrorist attack reflects a hardening of its position on cross-border terrorism and its potential impact on bilateral agreements. This move links the IWT to Pakistan's alleged support for terrorism, suggesting that the treaty's continuation is contingent upon Pakistan demonstrably abandoning its support for cross-border militant activities. The implications of Modi's critique and the subsequent developments are far-reaching. A reassessment of the IWT could have significant consequences for water management in both India and Pakistan, potentially impacting agricultural production, hydropower generation, and overall economic development. It could also exacerbate tensions between the two countries, particularly if India adopts a more assertive stance on water sharing or seeks to unilaterally modify the treaty's provisions. However, proponents of a revised approach argue that it is necessary to ensure India's water security and to address the changing realities of the Indus River basin. The debate over the IWT is not simply about water sharing; it is also about historical narratives, political ideologies, and national identity. Modi's critique of Nehru's legacy resonates with certain segments of the Indian population who believe that past governments were overly accommodating to Pakistan and that a more assertive approach is needed to protect India's interests. This narrative also aligns with the broader Hindu nationalist ideology that seeks to reclaim India's historical glory and to project its power on the global stage. However, critics of this approach caution against undermining the IWT, which has been largely successful in preventing water-related conflicts for over six decades. They argue that a unilateral revision of the treaty could have destabilizing consequences for the region and could undermine India's credibility as a responsible actor in international law. They also emphasize the importance of maintaining dialogue and cooperation with Pakistan, even in the face of political differences. In conclusion, the debate over the Indus Waters Treaty is a complex and multifaceted issue with far-reaching implications for India, Pakistan, and the wider region. Modi's critique of Nehru's legacy and the subsequent developments highlight the challenges of managing shared water resources in a context of political tensions, historical grievances, and changing environmental realities. A balanced approach is needed that takes into account India's water security concerns, the treaty's historical context, and the potential consequences of unilateral action. Ultimately, a sustainable solution requires dialogue, cooperation, and a commitment to resolving disputes through peaceful means.

The Indus Waters Treaty, despite being lauded as one of the most successful water-sharing agreements globally, has been a subject of intense scrutiny and debate, particularly in recent years. The core of the controversy revolves around the perceived imbalance in the allocation of water resources, with critics arguing that the treaty disproportionately favors Pakistan at the expense of India's agricultural and economic interests. This sentiment has been amplified by the current political climate, characterized by heightened nationalism and a more assertive foreign policy under Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Modi's remarks, directly questioning the treaty's benefits to India and attributing its perceived flaws to the decisions of former Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, have injected a new level of intensity into the debate. This criticism is not merely a reflection of contemporary political differences but also a revisiting of historical narratives and a re-evaluation of the Nehruvian legacy. The allegation that Nehru 'partitioned the country twice,' once through the Radcliffe Line and again through the IWT, is a powerful rhetorical device that frames the treaty as a historical injustice and a betrayal of India's national interests. This framing resonates with certain segments of the Indian population who view Nehru's policies as overly conciliatory towards Pakistan and who advocate for a more assertive approach to bilateral relations. The argument that the treaty allocated 80% of the Indus River's water to Pakistan is a central point of contention. Critics argue that this allocation deprived Indian farmers of much-needed irrigation water and hindered the development of water resources in the Indian states through which the Indus River flows. However, proponents of the treaty counter that the actual figures are more nuanced and that the treaty takes into account the specific needs of both countries. They also emphasize that the treaty has provisions for India to develop hydropower projects on the Western Rivers, subject to certain restrictions to protect Pakistan's water rights. The debate over the IWT is not solely about the allocation of water resources; it is also about the interpretation of historical events and the allocation of blame. The criticism of Nehru's decision-making process, particularly the allegation that he signed the treaty without proper parliamentary approval, is a significant point of contention. Critics argue that this lack of transparency and democratic process undermines the legitimacy of the treaty and that it should be re-evaluated in light of contemporary democratic norms. However, defenders of Nehru argue that the treaty was negotiated in good faith and that it reflected the prevailing political circumstances of the time. They also emphasize that the treaty was signed after extensive negotiations and with the support of the World Bank, which acted as a mediator between India and Pakistan. The legal dimensions of the IWT have also been subject to scrutiny, particularly in the context of India's rejection of the recent award issued by the Hague-based Court of Arbitration. India's argument that the court lacked jurisdiction and legitimacy underscores the complexities of international arbitration and the challenges of resolving disputes under bilateral treaties. This rejection also signals a willingness to challenge international legal interpretations that India perceives as detrimental to its national interests. The linkage of the IWT to cross-border terrorism represents a significant escalation of the debate. India's decision to place the treaty in abeyance following the Pahalgam terrorist attack reflects a hardening of its position on Pakistan and a determination to hold it accountable for its alleged support for terrorism. This linkage also raises questions about the future of bilateral agreements in the context of persistent cross-border tensions and the potential for non-state actors to disrupt peaceful relations between the two countries. The implications of a potential revision of the IWT are far-reaching. It could have significant consequences for water management in both India and Pakistan, potentially impacting agricultural production, hydropower generation, and overall economic development. It could also exacerbate tensions between the two countries and undermine the long-standing framework for cooperation on water resources. However, proponents of a revised approach argue that it is necessary to address India's water security concerns and to ensure that the treaty reflects the changing realities of the Indus River basin. A responsible and sustainable approach to the IWT requires a careful consideration of the historical context, the legal framework, and the potential consequences of any unilateral action. It also requires a commitment to dialogue and cooperation between India and Pakistan, even in the face of political differences. Ultimately, the long-term stability and prosperity of the region depend on the ability of both countries to manage their shared water resources in a fair and equitable manner.

The ongoing debate surrounding the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) transcends mere water allocation; it is deeply entwined with India's evolving foreign policy, national security considerations, and the reinterpretation of its historical narratives. Prime Minister Modi's critique of the treaty, framing it as an unfavorable agreement orchestrated by Jawaharlal Nehru, aligns with a broader strategy of questioning established paradigms and asserting a more assertive stance on matters of national interest. This revisionist approach is not limited to the IWT but extends to other historical events and policies, reflecting a desire to reshape India's self-perception and its role in the international arena. The emphasis on Nehru's alleged admission of the treaty's detrimental effects on India serves a dual purpose. Firstly, it challenges the legacy of a leader widely regarded as the architect of modern India, creating space for alternative perspectives and policy directions. Secondly, it provides justification for revisiting the IWT, arguing that the original agreement was flawed and requires correction to better serve India's interests. The claim that Nehru partitioned India twice – once through the Radcliffe Line and again through the IWT – is a potent narrative that resonates with nationalist sentiments. It positions the IWT as another instance of India compromising its sovereignty and resources, reinforcing the need for a more assertive approach in dealing with Pakistan. The specific allocation of 80% of the Indus River's water to Pakistan is consistently highlighted as evidence of the treaty's unfairness. While the actual figures and the complexities of water distribution are subject to debate, the perception of imbalance fuels calls for renegotiation and a more equitable arrangement. The criticism of Nehru's decision-making process, particularly the lack of parliamentary approval, raises important questions about democratic accountability and transparency in treaty negotiations. While the historical context of the 1960s must be considered, the emphasis on parliamentary approval reflects a contemporary concern for greater public involvement in decisions that have long-term implications for the nation. India's rejection of the Hague-based Court of Arbitration's award underscores a growing trend of questioning the legitimacy and competence of international judicial bodies. This skepticism reflects a broader concern about the influence of international institutions and a desire to assert greater control over decisions that affect India's sovereignty. The linkage of the IWT to cross-border terrorism represents a significant shift in India's approach to the treaty. By placing the IWT in abeyance following the Pahalgam attack, India signals its willingness to use the treaty as leverage to pressure Pakistan to cease its support for terrorism. This linkage raises complex questions about the relationship between bilateral agreements and national security concerns, and it sets a precedent for potentially linking other agreements to Pakistan's behavior. The potential consequences of a revision or abrogation of the IWT are far-reaching and require careful consideration. While India may seek to address its water security concerns and assert its rights to the Indus River's resources, any unilateral action could have destabilizing effects on the region and undermine India's reputation as a responsible international actor. A more sustainable approach would involve exploring options for renegotiation or modification of the treaty through dialogue and cooperation with Pakistan, while also addressing the underlying issues of water scarcity and climate change that are affecting the entire Indus River basin. The debate over the IWT also reflects broader trends in Indian foreign policy. Under Prime Minister Modi, India has adopted a more assertive and proactive approach, prioritizing national interests and challenging established norms. This approach is evident in India's stance on issues such as climate change, trade agreements, and regional security, and it is also reflected in the debate over the IWT. The future of the IWT remains uncertain, but it is clear that the treaty will continue to be a subject of intense debate and scrutiny. A responsible and sustainable approach requires a careful balancing of India's national interests, its international obligations, and the need for peaceful and cooperative relations with Pakistan. The long-term stability and prosperity of the region depend on the ability of both countries to manage their shared water resources in a manner that is fair, equitable, and sustainable.

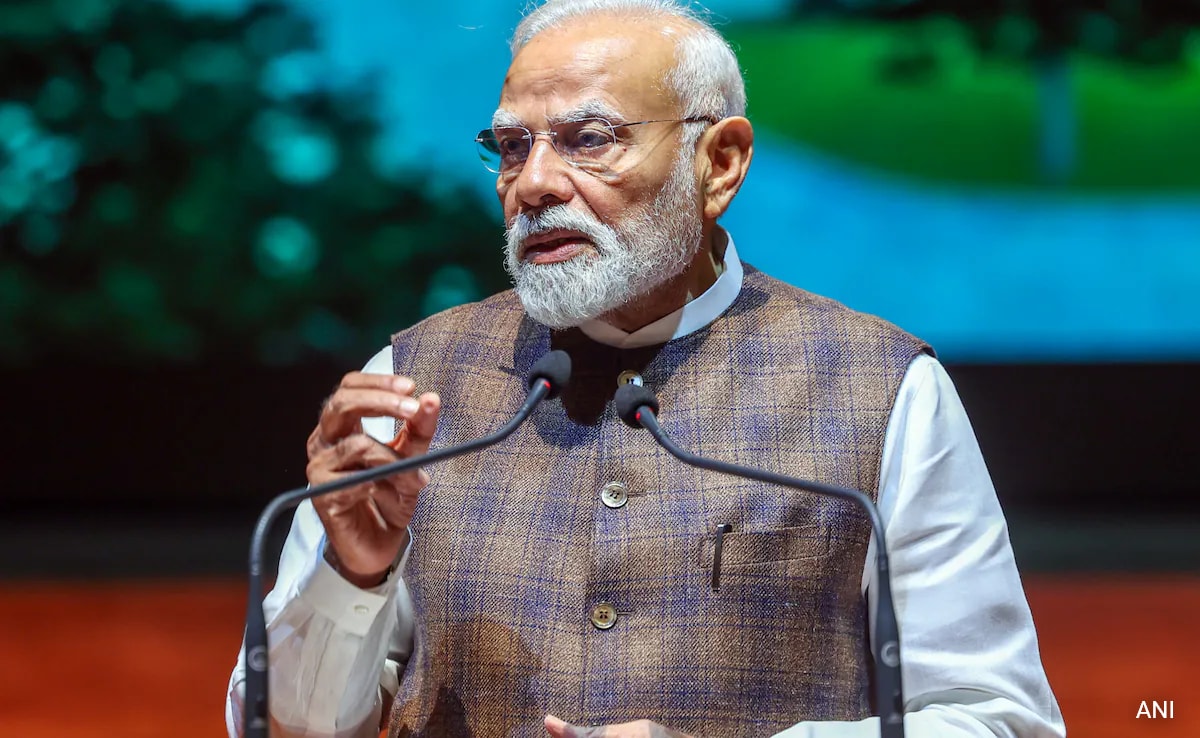

Source: "Nehru Admitted Indus Waters Treaty Brought No Benefit To India": PM Modi