|

|

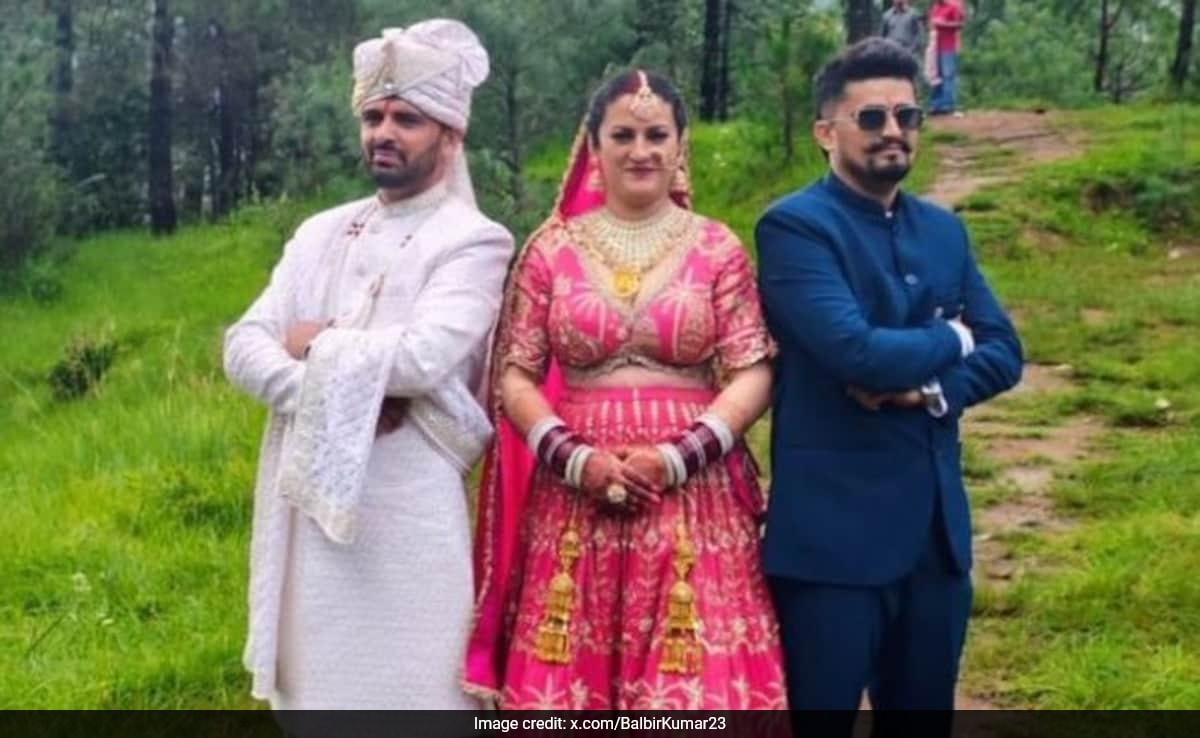

The article details a unique wedding ceremony in the Shillai village of Himachal Pradesh, where two brothers from the Hatti tribe married the same woman, Sunita Chauhan. This practice, known as polyandry, is an age-old tradition within the tribe, aimed at preserving familial land and ensuring stability within the community. The wedding, a vibrant affair filled with local folk songs and dances, lasted for three days and garnered significant attention online as videos of the ceremony went viral. The article presents the perspectives of both the bride and the grooms, emphasizing that the decision to enter into this marriage was made freely and without coercion. Sunita Chauhan, the bride, acknowledged her awareness of the tradition and expressed respect for the bond she shares with her husbands. Pradeep and Kapil Negi, the grooms, both affirmed their pride in upholding this tradition, with Kapil, who works abroad, stating his intention to provide support, stability, and love for their wife as a united family. This case highlights the complex interplay between tradition, modernization, and individual agency within a specific cultural context. The practice of polyandry, though less common now due to rising literacy and economic development, continues to be observed discreetly within the Hatti community and other tribal areas of Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand. This raises questions about the role of tradition in contemporary society and the extent to which individuals can and should deviate from established norms.

The Hatti tribe, a close-knit community residing along the Himachal Pradesh-Uttarakhand border, was officially recognized as a Scheduled Tribe three years ago. Polyandry, historically prevalent in this region, served various purposes, primarily revolving around the preservation of ancestral land. By having multiple brothers share a single wife, the division of land amongst heirs could be avoided, thus ensuring the continuity of the family's agricultural holdings. Moreover, the practice was seen as a way to promote brotherhood and mutual understanding within joint families, even when the brothers were born from different mothers. The tradition also provided a sense of security in a tribal society, where a larger family with more male members offered greater protection and resources. Managing scattered agricultural lands in the challenging hilly terrain required sustained effort, which a united family with multiple male members could more effectively provide. These factors contributed to the endurance of polyandry within the Hatti community for centuries. However, with increased access to education and economic opportunities, the prevalence of polyandry has declined, though it still persists in certain pockets of the region. The article also sheds light on the legal recognition of this tradition in Himachal Pradesh's revenue laws, where it is referred to as "Jodidara." This acknowledgment underscores the complex relationship between state law and customary practices within specific communities.

Kundan Singh Shastri, the general secretary of Kendriya Hatti Samiti, the primary organization representing the Hatti community, offers further insights into the rationale behind polyandry. He emphasizes that the tradition originated thousands of years ago as a means to prevent the fragmentation of agricultural land and to foster unity within families. He also highlights the sense of security that a larger, more male-dominated family provides in a tribal society, along with the practical benefits of having multiple individuals to manage the demanding agricultural tasks in the hilly terrain. The article details the wedding ceremony, known as "Jajda," where the bride is brought to the groom's village in a procession. The ritual, called "Seenj," takes place at the groom's residence, where a pandit chants mantras in the local language, sprinkles holy water on the couple, and offers them jaggery, symbolizing sweetness and blessings for their married life. The article concludes by noting that while these traditions are slowly fading, they continue to be practiced in some villages, reflecting the enduring influence of cultural heritage on contemporary life. The issue of tribal women's share in ancestral property remains a prominent concern. The article serves as a valuable snapshot of a unique cultural practice and the socio-economic factors that have shaped its evolution and persistence. It prompts further reflection on the challenges of preserving cultural traditions while navigating the forces of modernization and individual autonomy.

The narrative surrounding the Hatti tribe's practice of polyandry presents a microcosm of the larger global discourse on the preservation of cultural heritage in the face of modernization. While traditions like polyandry may appear unconventional from a Western perspective, they often serve deep-rooted social and economic purposes within their specific cultural contexts. In the case of the Hatti tribe, polyandry has historically functioned as a mechanism for maintaining land ownership, fostering familial unity, and ensuring the security of the community. However, as access to education and economic opportunities increases, traditional practices are inevitably challenged. The article suggests that the prevalence of polyandry is declining, albeit slowly, as younger generations are exposed to alternative lifestyles and values. This raises questions about the sustainability of such traditions in the long term and the extent to which they can adapt to changing social norms. The fact that the Hatti tribe's practice of polyandry is recognized within Himachal Pradesh's revenue laws is a testament to the complex interplay between state law and customary practices. This legal acknowledgment underscores the need for a nuanced approach to cultural preservation, one that respects the autonomy of communities while also ensuring the protection of individual rights. The article's emphasis on the bride's and grooms' voluntary participation in the marriage is crucial, as it highlights the importance of agency and consent in the perpetuation of traditional practices. Without genuine consent, such traditions can become tools of oppression and inequality. Therefore, it is essential to critically examine the power dynamics within these communities and to ensure that all members, particularly women, have the freedom to make informed choices about their lives.

Furthermore, the article touches upon the broader issue of gender equality within tribal communities. While polyandry may seem to challenge traditional notions of marriage, it is important to consider its implications for women's rights and agency. The article notes that the share of tribal women in ancestral property remains a significant concern. This suggests that despite the tradition of polyandry, women may still face systemic disadvantages in terms of property ownership and economic empowerment. Therefore, it is crucial to address these underlying inequalities in order to ensure that women have equal opportunities and rights within these communities. The article also raises questions about the potential benefits and drawbacks of polyandry for the individuals involved. While the tradition may offer certain advantages, such as economic security and familial support, it may also present challenges in terms of emotional intimacy and personal freedom. It is important to consider the perspectives of all members of the family, including the wife and the brothers, in order to fully understand the complexities of this practice. In conclusion, the article provides a fascinating glimpse into the Hatti tribe's practice of polyandry and the socio-economic factors that have shaped its evolution. It highlights the challenges of preserving cultural traditions in the face of modernization and the importance of addressing issues of gender equality and individual autonomy. The article serves as a reminder that cultural practices are not static but rather are constantly evolving in response to changing social and economic conditions. Therefore, it is essential to approach these traditions with a critical and nuanced perspective, one that recognizes both their historical significance and their potential implications for the individuals involved.

The article's discussion of the Hatti tribe's polyandry tradition extends beyond a mere description of an unusual marriage custom. It delves into the intricate web of socio-economic factors that have historically sustained this practice and the challenges it faces in a rapidly changing world. The emphasis on land preservation as a primary driver of polyandry sheds light on the critical role that agriculture plays in the tribe's economy and social structure. By limiting the division of land among multiple heirs, polyandry ensures that families can maintain their agricultural holdings and continue to derive their livelihoods from farming. This economic imperative is intertwined with the social goal of promoting familial unity and cooperation. By having multiple brothers share a single wife, the tradition fosters a sense of shared responsibility and mutual support within the family unit. This can be particularly important in the context of managing scattered agricultural lands in the difficult hilly terrain, where sustained effort and cooperation are essential for success. However, the article also acknowledges the challenges that polyandry poses to traditional notions of marriage and gender roles. While the bride and grooms in this particular case express their voluntary participation in the marriage, it is important to consider the potential for coercion and inequality within this practice. The article notes that the share of tribal women in ancestral property remains a significant concern, suggesting that women may still face systemic disadvantages despite the tradition of polyandry. Therefore, it is crucial to address these underlying inequalities and to ensure that women have equal opportunities and rights within these communities. The article's conclusion that polyandry is slowly declining due to rising literacy and economic development is consistent with broader trends in cultural change around the world. As societies become more interconnected and exposed to alternative lifestyles and values, traditional practices often face challenges to their survival. However, the fact that polyandry continues to be practiced in some villages of the Hatti tribe suggests that it retains a certain level of relevance and appeal for some members of the community.

The article's exploration of the Hatti tribe's polyandry tradition provides valuable insights into the complex interplay between culture, economics, and social change. The tradition, which has historically served as a mechanism for land preservation, familial unity, and security in a challenging environment, is now facing increasing pressures from modernization and globalization. The article's emphasis on the voluntary nature of the marriage is crucial, as it underscores the importance of individual agency and consent in the perpetuation of traditional practices. However, it also acknowledges the potential for coercion and inequality within this practice, particularly with regard to women's rights and property ownership. The article's analysis of the socio-economic factors that have contributed to the endurance of polyandry sheds light on the deep-rooted connections between cultural practices and the material conditions of life. The tradition's role in preventing the fragmentation of agricultural land highlights the critical importance of agriculture to the Hatti tribe's economy and social structure. The tradition's emphasis on familial unity and cooperation reflects the need for mutual support and shared responsibility in a challenging environment. The article's discussion of the challenges that polyandry faces from modernization and globalization underscores the broader trend of cultural change that is occurring around the world. As societies become more interconnected and exposed to alternative lifestyles and values, traditional practices often face increasing pressure to adapt or disappear. The article's conclusion that polyandry is slowly declining suggests that this trend is also affecting the Hatti tribe. However, the fact that polyandry continues to be practiced in some villages indicates that it retains a certain level of relevance and appeal for some members of the community. The long-term survival of this tradition will likely depend on its ability to adapt to changing social and economic conditions while preserving its core values and functions. It also necessitates protecting the rights and dignity of all involved, specially the tribal women.

Source: Two Brothers Marry Same Woman In Himachal Adopting Tribal Polyandry Tradition