|

|

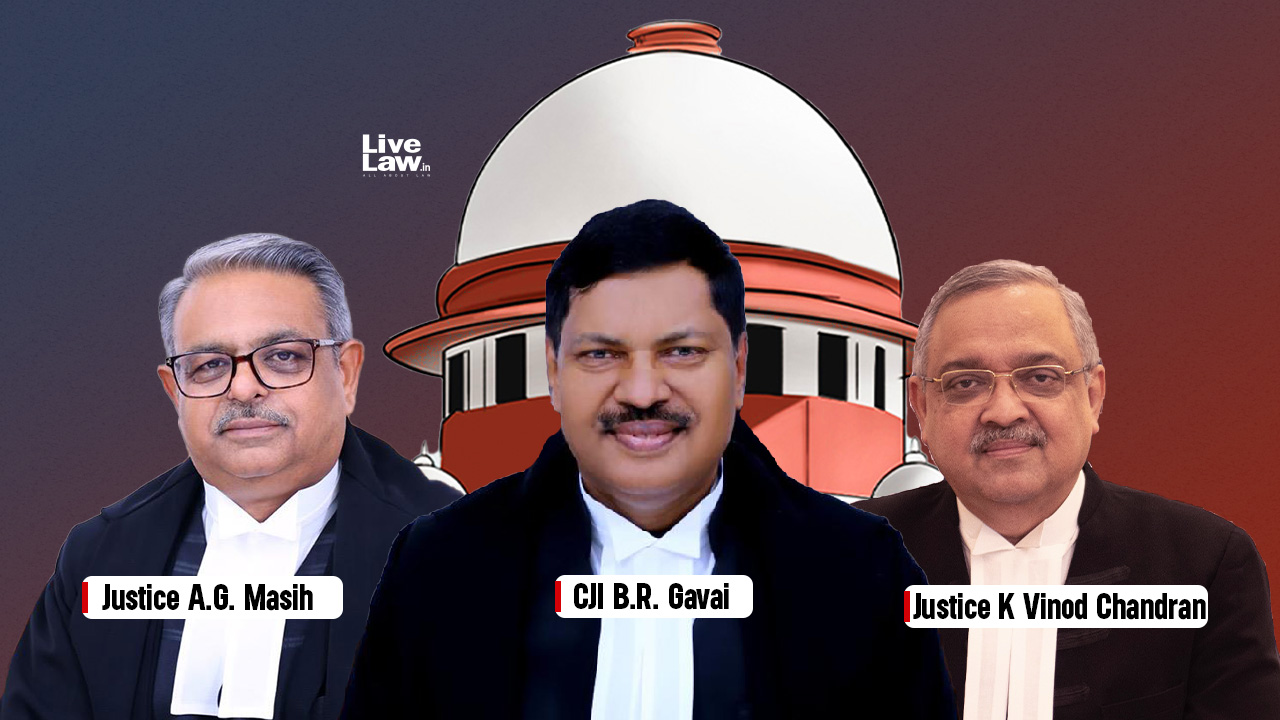

The Supreme Court of India has delivered a significant judgment reinstating the requirement of a minimum three-year practice as an advocate for candidates aspiring to enter judicial service at the entry-level. This decision, rendered on May 20, 2025, effectively overturns a previous directive from 2002 that had allowed fresh law graduates to directly apply for Munsiff-Magistrate posts without any prior practical experience at the bar. The ruling is poised to have a substantial impact on the recruitment processes of High Courts and State Governments across the country, mandating amendments to service rules to reflect this newly imposed condition. The Court explicitly stated that this requirement of a minimum three-year practice will not be applicable to recruitment processes already initiated by the High Courts before the date of the judgment. This provision ensures that candidates who have already applied under the previous rules are not unfairly disadvantaged by the sudden change in eligibility criteria. However, all future recruitment processes for the post of Civil Judge (Junior Division) will be subject to this mandatory practice requirement. To ensure compliance with the three-year practice requirement, the Supreme Court has outlined specific mechanisms for verification. Candidates must furnish a certificate duly certified by either the Principal Judicial Officer of the relevant court, or an advocate of that court with a minimum standing of ten years, duly endorsed by the Principal Judicial Officer of the district, or a Principal Judicial Officer of the station. This rigorous certification process aims to prevent the submission of fraudulent or inaccurate claims of practice, ensuring that only genuine and experienced advocates are considered for judicial service positions. For advocates practicing at the Supreme Court or the High Court, the Court has prescribed an alternative certification method. In these cases, a certificate issued by an advocate with a minimum standing of ten years, and endorsed by an officer designated by the Court, will be accepted as valid proof of practice. This alternative method acknowledges the unique circumstances of legal practice at the apex and High Courts, while maintaining the integrity and reliability of the verification process. Recognizing the value of diverse forms of legal experience, the Supreme Court has also directed that experience gained as law clerks with judges or judicial officers across the country be considered when calculating the total number of years of practice. This inclusion acknowledges the significant exposure and learning opportunities that law clerk positions provide, further enriching the pool of eligible candidates for judicial service. The decision was delivered by a bench comprising Chief Justice of India BR Gavai, Justice AG Masih, and Justice K Vinod Chandran, in the All India Judges Association case. The judgment also addressed directions regarding the promotion quota for Limited Departmental Competitive Exams, marking a comprehensive resolution to several outstanding issues pertaining to judicial recruitment and career advancement. The reinstatement of the minimum practice requirement stems from concerns raised by various High Courts, legal professionals, and the bench itself, regarding the effectiveness of recruiting fresh law graduates without any practical experience. Over the past two decades, the Court observed, the recruitment of fresh law graduates into judicial service has not been a universally successful experience. The Court noted that judges, from the very day they assume office, deal with critical issues concerning life, liberty, property, and reputation. Theoretical knowledge gained from law books and pre-service training, the Court emphasized, cannot adequately substitute the firsthand experience of the working of the court system and the administration of justice. This practical exposure is crucial for candidates to understand the intricacies of a judge's role and responsibilities.

The Supreme Court’s judgment highlights the importance of practical experience in shaping competent and effective judicial officers. The Court articulated that the observation of lawyers and judges functioning within the court system provides invaluable insights that cannot be replicated through academic study alone. This exposure allows candidates to develop a deeper understanding of the ethical considerations, procedural complexities, and practical challenges inherent in the judicial process. The decision to reinstate the minimum practice requirement reflects a growing consensus among High Courts and legal experts that prior practical experience is essential for efficient functioning as judicial officers. Many High Courts and States have expressed the view that the entry of fresh law graduates into judicial service has been "counter-productive," leading to inefficiencies and other challenges. Only Sikkim and Chhattisgarh High Courts have explicitly stated that the three-year practice requirement need not be restored. The current judgment effectively reverses the 2002 decision in the All India Judges Association case, which had eliminated the minimum practice requirement. In that earlier judgment, the Supreme Court had observed that the best legal talent was not being attracted to judicial service, as bright young law graduates with three years of practice found the positions unattractive. The Shetty Commission, after considering the views of various authorities, had recommended that the practice requirement be removed to attract a wider pool of candidates. However, the Supreme Court has now reconsidered its earlier position, acknowledging the challenges and concerns that have emerged over the past two decades. The Court has recognized that while attracting talent is important, ensuring that judicial officers possess a solid foundation of practical experience is paramount to maintaining the integrity and effectiveness of the judiciary. The judgment also sheds light on the debates and deliberations that took place during the hearing of the case. Amicus Curiae, Senior Advocate Siddharth Bhatnagar, raised concerns about allowing fresh law graduates entry to the judicial service without any practical experience as an advocate. The bench also shared similar concerns, acknowledging the potential risks associated with appointing inexperienced individuals to positions of significant judicial responsibility. However, the bench also deliberated on the potential effectiveness of the practice period, acknowledging that some aspirants might merely engage in pro forma practice, signing vakalaths without gaining meaningful experience. Despite these concerns, the Court ultimately concluded that a minimum practice requirement, coupled with robust certification procedures, remains the most effective way to ensure that judicial officers possess the necessary skills and experience to perform their duties effectively.

The Supreme Court's decision to reinstate the minimum practice requirement for judicial service entry marks a significant shift in the approach to judicial recruitment in India. It reflects a renewed emphasis on the importance of practical experience in shaping competent and effective judicial officers. While the decision may initially limit the pool of eligible candidates, it is expected to ultimately strengthen the judiciary by ensuring that those appointed to judicial positions possess a solid foundation of practical knowledge and skills. The requirement for certification of practice by senior members of the bar and judicial officers aims to prevent candidates from merely going through the motions to fulfil the requirement. This process will ensure a reasonable amount of diligence from applicants. The allowance for consideration of law clerk experience as contributing towards the requirement of 3 years aims at creating a level playing field for prospective judicial officers. The court, in its wisdom, took a balanced approach to allow such exposure as a beneficial method of experience building. The immediate effect of the Supreme Court's judgment will be the amendment of service rules by all High Courts and State Governments to incorporate the mandatory three-year practice requirement. This process is expected to be completed in the coming months, paving the way for the implementation of the new rules in future recruitment processes. The decision may also prompt High Courts and State Governments to review their existing training programs for newly recruited judicial officers, ensuring that these programs adequately address the practical skills and knowledge that are essential for effective judicial performance. Furthermore, the Supreme Court's judgment may encourage law schools to enhance their clinical legal education programs, providing students with more opportunities to gain practical experience before graduation. This could include internships, moot court competitions, and other activities that simulate the real-world challenges of legal practice. Overall, the Supreme Court's decision is expected to have a far-reaching impact on the Indian legal system, strengthening the judiciary and ensuring that it remains a vital pillar of democracy. The decision emphasizes that while academic qualifications are important, they are not sufficient to equip individuals with the skills and experience necessary to effectively administer justice. By prioritizing practical experience, the Supreme Court aims to create a more competent, effective, and ethical judiciary that is better equipped to serve the needs of the Indian people.

Source: Supreme Court Mandates Minimum Practice As Advocate To Enter Judicial Service