|

|

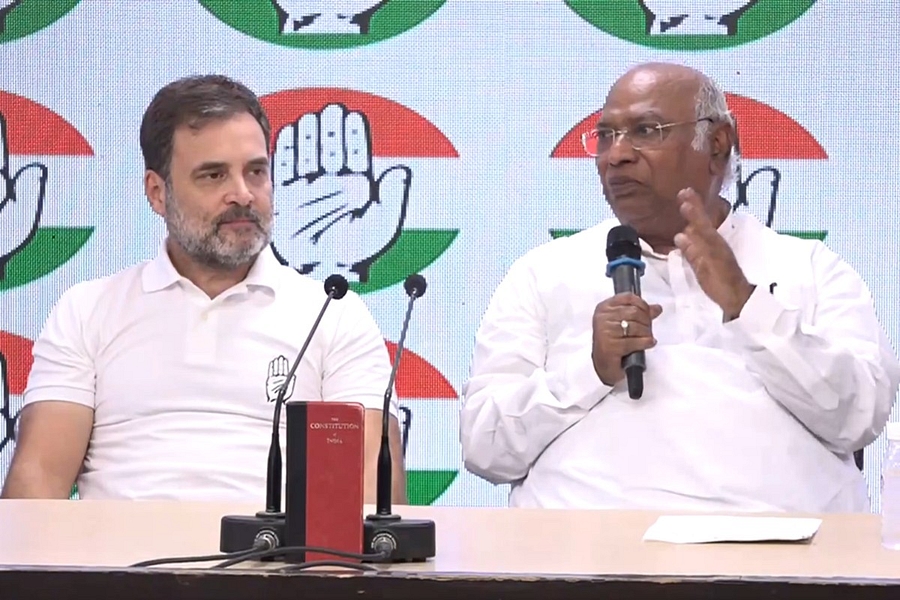

The recent letter from Congress President Mallikarjun Kharge to Prime Minister Narendra Modi concerning the proposed caste survey by the Union Government marks a significant moment in India's ongoing discourse on social justice, equity, and representation. Kharge's appeal, while ostensibly focused on the methodology of the caste survey, delves deeper into the fundamental issues of caste-based discrimination, the limitations of existing reservation policies, and the need for a more comprehensive approach to address historical inequalities. His suggestion to emulate the Telangana model, rather than his own state of Karnataka which initiated a caste survey first, highlights a strategic political calculation, potentially aimed at showcasing Congress-ruled states as effective implementers of social justice measures while subtly critiquing the BJP's handling of the issue. The core of Kharge’s argument revolves around the necessity of a robust and accurate caste census to inform policy decisions and ensure that marginalized communities receive their due share of resources and opportunities. He criticizes the arbitrarily imposed 50 percent ceiling on reservations, arguing that it is an outdated constraint that hinders the effective implementation of affirmative action. By advocating for reservations in private educational institutions, Kharge is attempting to expand the scope of reservation policies beyond the public sector, acknowledging the growing importance of private institutions in shaping the educational landscape and opportunities for social mobility. The demand for a dialogue with all political parties underscores the contentious nature of the caste census issue and the need for a broad consensus to avoid further polarization. Kharge’s assertion that a caste census should not be viewed as divisive is a direct response to concerns that it could exacerbate social divisions and reinforce caste identities. He frames it as a crucial tool for empowering marginalized communities and ensuring their rights are protected. Finally, his critique of the BJP’s past opposition to the caste census highlights the shifting political dynamics surrounding the issue, suggesting that the ruling party has been compelled to acknowledge the demand for social justice and empowerment due to political pressure and the growing awareness of caste-based inequalities.

The complexities surrounding the implementation of a caste census in India are multifaceted, encompassing logistical, political, and social considerations. The last caste-based census was conducted in 1931, and the absence of reliable data on caste demographics has hindered the effective implementation of policies aimed at addressing caste-based discrimination and promoting social equity. The Socio-Economic Caste Census (SECC) conducted in 2011 was marred by inaccuracies and methodological flaws, rendering it largely unusable for policy purposes. A comprehensive and accurate caste census is essential for understanding the socio-economic conditions of different caste groups, identifying disparities in access to education, employment, and other resources, and designing targeted interventions to address these inequalities. However, the process of conducting a caste census is fraught with challenges. Defining caste categories, ensuring accurate self-identification, and preventing manipulation of data are significant hurdles. Moreover, the political sensitivities surrounding caste make it difficult to achieve a broad consensus on the methodology and objectives of the census. Concerns have been raised that a caste census could reinforce caste identities and exacerbate social divisions, leading to increased competition for resources and political power. On the other hand, proponents argue that a caste census is necessary to address historical injustices and ensure that marginalized communities receive their fair share of representation and resources. Without accurate data on caste demographics, it is impossible to effectively monitor the implementation of reservation policies and assess their impact on social equity. The 50 percent ceiling on reservations, which was established by the Supreme Court in the Indra Sawhney case, has been a major constraint on the implementation of affirmative action policies. Many argue that this ceiling is arbitrary and does not adequately reflect the proportion of backward classes in the population. Kharge's demand for its removal reflects a growing consensus that the existing reservation framework needs to be re-evaluated to ensure that it effectively addresses the needs of marginalized communities.

The Telangana model for caste survey, which Kharge advocates, likely involves a detailed and comprehensive methodology for data collection and analysis, potentially including specific questionnaires and protocols designed to accurately capture caste identities and socio-economic conditions. The specific details of the Telangana model would need to be examined to fully assess its strengths and weaknesses. However, the key takeaway is that Kharge sees it as a viable and effective approach for conducting a caste census at the national level. The issue of reservations in private educational institutions is particularly contentious. While reservation policies have traditionally been applied to public institutions, the increasing role of private institutions in education has raised questions about whether they should also be subject to reservation quotas. Arguments in favor of reservations in private institutions center on the idea that access to quality education is essential for social mobility and that private institutions should not be allowed to perpetuate caste-based inequalities. Opponents argue that extending reservations to private institutions could undermine their autonomy and academic standards. They also raise concerns about the potential for reverse discrimination and the impact on meritocracy. The debate over reservations in private institutions highlights the complex trade-offs involved in balancing the goals of social equity and individual freedom. Finding a solution that is both fair and effective requires careful consideration of the specific context and the potential consequences of different policy options. Kharge's call for a dialogue with all political parties is crucial for building a consensus on the way forward. The caste census issue is too important and too sensitive to be decided unilaterally. A broad-based dialogue can help to address concerns, build trust, and ensure that the outcome is seen as legitimate and fair by all stakeholders. Ultimately, the success of any caste census and reservation policy will depend on the political will to implement it effectively and the commitment to addressing the underlying causes of caste-based discrimination.

Furthermore, the historical context of caste in India is deeply rooted in the socio-economic and political fabric of the nation. The caste system, traditionally based on occupation and social hierarchy, has been a source of profound inequality and discrimination for centuries. Despite legal reforms and affirmative action policies, caste continues to play a significant role in shaping life chances and opportunities for millions of Indians. The persistence of caste-based discrimination is evident in various aspects of life, including access to education, employment, housing, and healthcare. Dalits (formerly known as untouchables), who are at the bottom of the caste hierarchy, continue to face systemic discrimination and violence. Other backward classes (OBCs) also experience significant disadvantages compared to upper-caste groups. Addressing these inequalities requires a multi-pronged approach that includes legal reforms, affirmative action policies, and social awareness campaigns. A caste census is an essential tool for understanding the extent and nature of caste-based disparities and for designing targeted interventions to address them. However, it is important to recognize that a caste census alone will not solve the problem of caste-based discrimination. It must be accompanied by a broader effort to challenge caste prejudices, promote social inclusion, and empower marginalized communities. The role of education is crucial in this regard. Schools and universities must teach students about the history of caste and the importance of social justice. Curricula should be designed to promote empathy, understanding, and respect for diversity. Media also has a responsibility to portray marginalized communities in a positive light and to challenge stereotypes and prejudices. In addition to education and media, civil society organizations and community leaders play a vital role in promoting social inclusion and advocating for the rights of marginalized communities. They can work to raise awareness about caste-based discrimination, provide support to victims of discrimination, and lobby for policy changes. Finally, political leaders must demonstrate a commitment to social justice and equality. They must speak out against caste-based discrimination and promote policies that benefit all members of society, regardless of their caste. The challenge of addressing caste-based discrimination in India is immense, but it is not insurmountable. By working together, we can create a more just and equitable society where everyone has the opportunity to reach their full potential.

The economic implications of caste-based discrimination are significant. Studies have shown that caste-based inequalities contribute to lower levels of economic development and productivity. When a large segment of the population is excluded from opportunities due to their caste, it reduces the overall pool of talent and limits economic growth. Caste-based discrimination also leads to lower levels of social mobility. People from marginalized castes are less likely to be able to climb the economic ladder, perpetuating cycles of poverty and inequality. This has a negative impact on their families and communities. Addressing caste-based economic inequalities requires a combination of policies and programs. Affirmative action policies, such as reservations in education and employment, can help to level the playing field and provide opportunities for people from marginalized castes. However, these policies must be carefully designed and implemented to avoid unintended consequences. In addition to affirmative action, it is important to invest in education and skills training for people from marginalized castes. This will help them to acquire the skills and knowledge they need to compete in the modern economy. It is also important to promote entrepreneurship and create opportunities for people from marginalized castes to start their own businesses. Access to credit and capital is essential for entrepreneurs, and special programs can be designed to provide financial assistance to people from marginalized castes. Finally, it is important to address systemic barriers to economic participation that are faced by people from marginalized castes. This includes discrimination in the labor market, unequal access to resources, and lack of representation in decision-making bodies. By addressing these barriers, we can create a more level playing field and ensure that everyone has the opportunity to participate in the economy. The role of the private sector is also crucial in promoting economic inclusion. Companies can implement policies to ensure that their workforce is diverse and inclusive. They can also support programs that provide education and skills training to people from marginalized castes. By working together, the public and private sectors can create a more equitable and prosperous society for all.

The legal framework for addressing caste-based discrimination in India is complex and evolving. The Constitution of India prohibits discrimination on the basis of caste and provides for affirmative action to protect the interests of marginalized castes. The Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989, is a landmark legislation that aims to prevent and punish atrocities against Dalits and Adivasis. However, the implementation of this law has been uneven, and many cases of caste-based violence go unpunished. There is a need for greater accountability and enforcement of the law to ensure that victims of caste-based violence receive justice. In addition to the Prevention of Atrocities Act, there are other laws and regulations that address caste-based discrimination in specific areas, such as education and employment. However, these laws are often fragmented and incomplete, and there is a need for a more comprehensive and integrated legal framework. The judiciary has played an important role in interpreting and enforcing the constitutional provisions on caste-based discrimination. Landmark Supreme Court judgments have clarified the scope of affirmative action and upheld the validity of reservation policies. However, the judiciary has also been criticized for its cautious approach to caste-based issues and its reluctance to challenge entrenched power structures. There is a need for greater judicial activism to protect the rights of marginalized castes and ensure that the legal system is truly accessible to all. The role of human rights organizations is also crucial in monitoring the implementation of anti-discrimination laws and advocating for the rights of marginalized communities. These organizations can help to raise awareness about caste-based discrimination, provide legal assistance to victims of discrimination, and lobby for policy changes. By working together, the legal community, human rights organizations, and the judiciary can create a more just and equitable legal system that protects the rights of all members of society, regardless of their caste.

The international context of caste-based discrimination is also important to consider. Caste-based discrimination is not unique to India. It exists in other parts of South Asia and in the diaspora. The United Nations has recognized caste-based discrimination as a form of racial discrimination and has called on states to take measures to eliminate it. The international community has a role to play in supporting efforts to address caste-based discrimination in India and other parts of the world. International organizations can provide technical assistance and financial support to programs that promote social inclusion and empower marginalized communities. They can also monitor the implementation of international human rights standards and hold states accountable for their obligations. The diaspora community can also play a role in raising awareness about caste-based discrimination and advocating for policy changes. Members of the diaspora can use their influence to lobby governments and international organizations to take action to address caste-based discrimination. By working together, the international community can help to create a more just and equitable world where everyone has the opportunity to reach their full potential, regardless of their caste. The challenges of addressing caste-based discrimination are complex and multifaceted, but they are not insurmountable. By working together, we can create a more just and equitable society for all. The first step is to acknowledge the existence of caste-based discrimination and to recognize its impact on the lives of millions of people. The second step is to commit to taking action to address caste-based discrimination. This includes implementing policies to promote social inclusion, investing in education and skills training for people from marginalized castes, and challenging stereotypes and prejudices. The third step is to hold ourselves accountable for our actions and to ensure that we are making progress towards achieving a more just and equitable society. By taking these steps, we can create a future where everyone has the opportunity to reach their full potential, regardless of their caste.