|

|

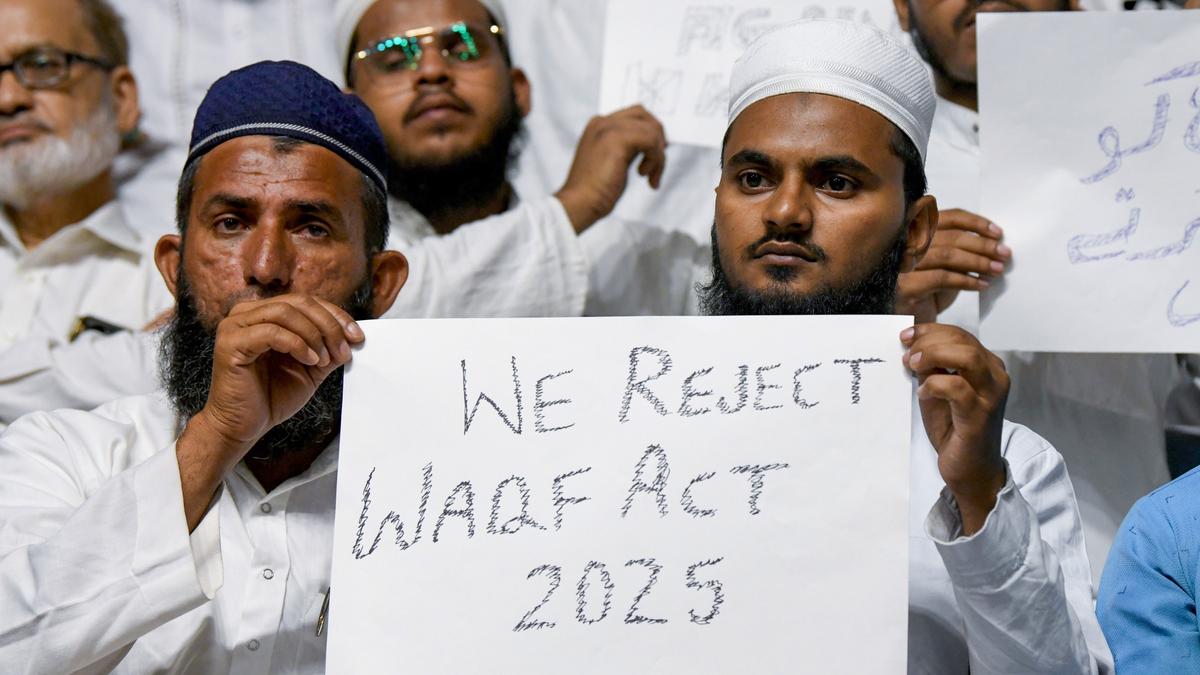

The legal landscape surrounding Waqf properties in India is undergoing significant scrutiny, particularly with the enactment of the Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025. The Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK), a prominent political party in Tamil Nadu, has voiced strong concerns regarding the impartiality of the Joint Parliamentary Committee (JPC) proceedings that led to the amendments. These concerns, articulated in a rejoinder affidavit filed before the Supreme Court, highlight the DMK's apprehension that communal interests may have unduly influenced the deliberations, potentially jeopardizing the fundamental rights of individuals based on their religious identity. The crux of the DMK's argument rests on the assertion that a vast majority – approximately 95% – of the stakeholders who appeared before the JPC expressed staunch opposition to the Bill. In contrast, the remaining 5% who supported the Bill were allegedly representing communal interests or operating under communal banners, raising serious questions about the representativeness and objectivity of the process. This disparity in stakeholder perspectives underscores the contentious nature of the Waqf amendments and the potential for them to disproportionately impact certain segments of the population. The Indian Union Muslim League (IUML), a key political organization from Kerala, has echoed the DMK's concerns, further amplifying the opposition to the Act. The IUML's affidavit raises alarm about the potential for a large number of properties, including mosques, graveyards, orphanages, and schools, to lose their status as Waqf properties and become subject to takeover by the Union government. This fear of governmental encroachment on religiously significant properties highlights the delicate balance between state power and religious freedom in the context of Waqf administration. The DMK's legal challenge extends beyond questioning the procedural integrity of the JPC proceedings. The party argues that the mere enactment of the Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025, does not shield it from constitutional review. The DMK contends that the Act's provisions, if allowed to stand, could result in manifest injustice and deprivation of fundamental rights, particularly those pertaining to religious identity. This argument centers on the principle that even legislation passed by Parliament must be subjected to rigorous constitutional scrutiny, especially when it is alleged to infringe upon fundamental rights enshrined in the Constitution. The DMK's emphasis on the potential for irreversible consequences underscores the urgency of the matter. The party argues that allowing the Act to remain in effect, even for a limited period, would permanently alter legal rights and the status of properties, thereby causing irreparable harm. In contrast, a temporary stay would merely maintain the status quo, ensuring that no irreversible prejudice or harm is caused before the constitutionality of the Act's provisions is fully adjudicated. This argument highlights the importance of interim relief in safeguarding fundamental rights while the courts deliberate on the merits of the case. The legal arguments presented by the DMK and the IUML also challenge the Union government's claim that registration of Waqf-by-user properties is mandatory. The DMK argues that the Waqf Act, 1923, the Waqf Act, 1954, and the Waqf Act, 1995, as they stood prior to the 2025 amendments, required applicants to furnish particulars within their knowledge, such as the description of properties, annual income, and the nature and object of the Waqf. However, there was no statutory mandate to furnish information that is incapable of being ascertained, such as the name of the original settlor in Waqfs by user created centuries ago. This argument challenges the government's assertion that the 2025 Act merely clarifies existing law, contending that it imposes new and onerous requirements that are impossible to fulfill for many Waqfs-by-user. The DMK further argues that Waqf-by-user does not depend on registration for its legal status as a Waqf. This argument is crucial because it challenges the government's attempt to invalidate Waqfs-by-user that have not been formally registered. The DMK asserts that the 2025 Act, by denying recognition to Waqfs-by-user and mandating impossible preconditions for centuries-old endowments, strikes at the heart of the religious freedom guaranteed by the Constitution. This argument frames the issue as a fundamental clash between the government's power to regulate Waqf properties and the constitutional right to religious freedom. The government, on the other hand, defends the 2025 Act by arguing that rampant encroachments in the name of Waqfs necessitated the amendments. The Centre claims that intrusions into private and government properties through misuse of earlier Waqf provisions led to a phenomenal 116% rise in Waqf lands from 2013 to 2024, a high unmatched even during the Mughal period. This argument seeks to justify the amendments as a necessary measure to curb illegal land grabbing and protect private and government properties. The government's argument implicitly suggests that the earlier Waqf laws were susceptible to abuse and that the 2025 Act is designed to prevent further misuse. The Supreme Court, in its initial hearing on the matter, recorded an assurance by the government to neither denotify any Waqf property, including Waqfs-by-user ones, nor make any appointment of non-Muslims to the Central Waqf Council or the States Waqf Boards under the 2025 Act. This assurance, while providing some temporary relief, does not address the underlying constitutional concerns raised by the DMK and the IUML. The legal battle surrounding the Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025, is likely to continue in the Supreme Court, with the court tasked with balancing the government's interest in regulating Waqf properties with the constitutional rights of religious minorities.

The arguments presented by both sides highlight the complex interplay of legal, religious, and political factors that shape the debate over Waqf administration in India. The government's focus on preventing encroachments and misuse of Waqf properties reflects a broader concern with maintaining law and order and protecting public resources. However, the DMK and the IUML's emphasis on protecting the religious freedom of minorities underscores the importance of ensuring that any regulatory measures are narrowly tailored and do not unduly burden religious practices or institutions. The legal concept of 'Waqf-by-user' is central to the dispute. This refers to properties that have been traditionally used for religious or charitable purposes by the Muslim community, even if they have not been formally registered as Waqf properties. The DMK argues that the 2025 Act unfairly penalizes Waqfs-by-user by requiring them to meet onerous registration requirements that are often impossible to fulfill due to the passage of time and the lack of documentation. The government, on the other hand, argues that all Waqf properties, including Waqfs-by-user, should be subject to registration to ensure transparency and accountability. The outcome of the legal challenge to the Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025, could have significant implications for the management and control of Waqf properties across India. If the Supreme Court upholds the Act, it could lead to a greater degree of governmental control over Waqf properties and potentially result in the loss of Waqf status for many properties that have not been formally registered. Conversely, if the Supreme Court strikes down or modifies the Act, it could reaffirm the autonomy of Waqf boards and protect the religious freedom of minorities. The case also raises important questions about the role of parliamentary committees in the legislative process. The DMK's allegations of bias and undue influence in the JPC proceedings underscore the need for transparency and impartiality in the deliberations of such committees. The legal challenge to the Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025, is not simply a legal dispute; it is a reflection of broader societal tensions over religious freedom, minority rights, and the role of the state in regulating religious institutions. The Supreme Court's decision in this case will have a profound impact on the lives of millions of Muslims in India and will shape the future of Waqf administration in the country. Furthermore, the differing perspectives presented by the DMK, IUML, and the Union government reflect the diverse political landscape of India. The DMK and IUML, representing regional interests and minority concerns, are challenging the central government's authority and advocating for the protection of religious freedom. The Union government, on the other hand, is asserting its power to regulate Waqf properties in the name of national security and economic development. The legal battle over the Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025, is therefore a microcosm of the broader power struggles and ideological clashes that characterize Indian politics. The debate surrounding the Act also brings to the forefront the issue of secularism in India. The government's intervention in Waqf administration raises questions about the extent to which the state can legitimately interfere in religious matters. While the government argues that its actions are necessary to prevent misuse and corruption, critics contend that such intervention violates the principles of secularism and religious neutrality. The Supreme Court's decision in this case will likely provide further clarification on the meaning and scope of secularism in the context of Indian law. In addition to the legal and political dimensions, the Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025, also has significant economic implications. Waqf properties often generate substantial income, which is used to fund religious and charitable activities. The government's control over Waqf properties could therefore affect the financial resources available to Muslim religious institutions and charitable organizations. The DMK and IUML's concerns about the potential loss of Waqf properties highlight the economic stakes involved in this dispute. The control over Waqf properties represents a significant source of power and influence, and the government's attempt to assert greater control over these properties is likely to be resisted by those who stand to lose out. The legal challenge to the Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025, is therefore a multifaceted issue with legal, religious, political, and economic dimensions. The Supreme Court's decision in this case will have far-reaching consequences for the Muslim community in India and will shape the future of Waqf administration in the country for decades to come.

The core of the controversy surrounding the Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025, lies in the conflicting interpretations of the role of the state in relation to religious institutions and the extent to which the government can legitimately regulate religious affairs. The Union government's justification for the amendments centers on the need to prevent encroachment and misuse of Waqf properties, arguing that the earlier laws were insufficient to address these issues. This perspective emphasizes the government's responsibility to maintain law and order, protect public resources, and ensure accountability in the management of public assets. However, the DMK and IUML challenge this perspective by arguing that the amendments infringe upon the religious freedom of minorities and undermine the autonomy of Waqf boards. They contend that the government's actions are driven by a desire to exert greater control over Muslim religious institutions and that the amendments impose unreasonable burdens on Waqfs, particularly Waqfs-by-user. The legal arguments presented by both sides reflect these differing interpretations of the relationship between the state and religion. The government relies on the principle that all property, including religious property, is subject to state regulation and that the government has a legitimate interest in preventing misuse and corruption. The DMK and IUML, on the other hand, argue that religious institutions enjoy a degree of autonomy from state interference and that the government must respect the religious freedom of minorities. The constitutional framework of India provides a complex and nuanced approach to the relationship between the state and religion. The Constitution guarantees the right to freedom of religion, but it also allows the state to regulate religious institutions in the interest of public order, morality, and health. The Supreme Court has consistently held that the state can regulate the secular aspects of religious institutions, but it cannot interfere with the essential religious practices of any religion. The legal challenge to the Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025, requires the Supreme Court to apply these principles to the specific context of Waqf administration. The court must determine whether the amendments are a legitimate exercise of the state's power to regulate religious institutions or whether they infringe upon the religious freedom of Muslims and undermine the autonomy of Waqf boards. The outcome of the case will depend on the court's interpretation of the constitutional provisions relating to religious freedom and the balance it strikes between the state's interest in regulation and the individual's right to religious practice. The debate surrounding the Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025, also raises important questions about the role of historical context in interpreting legal and constitutional provisions. The Waqf system has a long and complex history in India, dating back to the Mughal period. The system was originally designed to provide for the religious and charitable needs of the Muslim community, and Waqf properties were often endowed by wealthy individuals for these purposes. Over time, the Waqf system became increasingly complex and bureaucratic, and there were instances of mismanagement and corruption. The government's intervention in Waqf administration has been justified, in part, by the need to address these historical problems. However, the DMK and IUML argue that the government's actions ignore the historical context of the Waqf system and fail to recognize the importance of preserving the autonomy of Waqf boards. They contend that the amendments impose a uniform regulatory framework on all Waqfs, regardless of their historical origins or their specific needs. The Supreme Court's decision in this case will likely take into account the historical context of the Waqf system and the need to balance the government's interest in regulation with the preservation of the cultural and religious heritage of the Muslim community. In conclusion, the legal challenge to the Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025, is a complex and multifaceted issue with legal, religious, political, economic, and historical dimensions. The Supreme Court's decision in this case will have far-reaching consequences for the Muslim community in India and will shape the future of Waqf administration in the country for decades to come. The court's decision will also provide further clarification on the meaning and scope of secularism in the context of Indian law and the balance between the state's interest in regulation and the individual's right to religious practice.

Source: On SC’s Waqf hearing eve, DMK says 95% stakeholders before JPC was against amendments